First published on 09/05/2013, and last updated on 03/05/2018

By: Morvarid Kamali, Cenesta (Member)

The history of conservation and sustainable use in many parts of the world is much older than government-managed protected areas, yet indigenous peoples’ and community conserved areas and territories are often neglected or not recognised in official conservation systems. However, in the last decade or so, ICCAs, as a bio-cultural or eco-cultural conservation phenomenon, have gained significant recognition at international levels. This also builds on earlier and ongoing development in the fields of human rights, indigenous rights, cultural heritage, participatory development, decentralized governance, and so on; these socio-cultural, economic and political contexts being crucial to the emergence, sustenance, and strengthening of ICCAs.

Like many other countries, Iran has innumerable ICCAs that are increasingly being understood, recognised and supported. This is in response to both domestic demand and the realization of the importance of ICCAs and of the need to meet obligations under international instruments and commitments. Thus, Iran’s natural resource managers in the government and other decision-making sectors are highly encouraged to carefully take into account, document and support ICCAs and involve indigenous peoples in decision- making, and then officially recognise and empower them by giving them a more active role in nature conservation.

The indigenous peoples and local/traditional communities of Iran are highly organized in terms of social structure and major decisions are taken by the Elders who are appointed based on merit and communities’ trust. They have their own traditional norms and customary practices (such as qorukh, yurd, kham) and unique spiritual beliefs regarding natural resources. These systems have sustained their way of life for thousands of years, but in the recent past, have been forced to face issues that threaten their very existence. Chief among these threats is the induced weakening of the tribal governance systems and the resultant fragmentation of their territorial ICCAs, as well as the overuse of their rangelands.

In recent years, following the national and international efforts for the recognition of ICCAs and community rights and the establishment of tribal community investment funds and indigenous peoples’ federations and unions (such as UNINOMAD), such recognition has steadily gained ground. Conservation and livelihoods projects have concomitantly brought about some hopeful results. For instance, an action plan prepared jointly by civil society organisations, indigenous peoples, the Iranian Forests, Rangelands & Watershed Management Organisation (FRWMO) and the Iranian Department of Environment (DoE) led to territory-based ICCAs to be included in the Law of the Fifth Five-Year Development Plan. This was accompanied by numerous declarations and commitments by FRWO top administrators in support of nomadic and local communities’ ICCAs and by the de facto acceptance of ICCAs by government through GEF-SGP projects. On the ground, which is what counts the most, we can mention that the Namdan Plain Wetland ICCA and the ICCA of the Farrokhvand tribe of Bakhtiari tribal confederacy have been recognised and legally protected by the DoE.

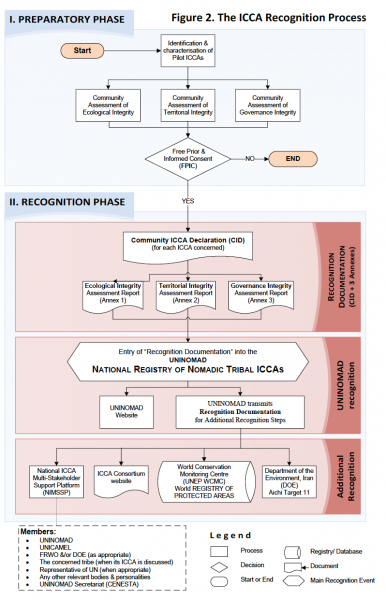

This progress is enabled by sharing experience on effective mechanisms for stakeholder involvement, widening governance types in conservation, and combining the traditional and indigenous know-how with scientific knowledge. Also, new approaches and concepts are being used in natural resource management such as: the Territory-Based Sustainable Range Management Programme (TBSRM); Non-Equilibrium Ecosystems (NEE) science; and the IUCN protected area governance ‘type D’ (ICCAs), as well as innovative mechanisms that involve recognition by a hierarchy of structures ranging from a Community Declaration on ICCAs through UNINOMAD and relevant CSOs to a National Multi-Stakeholder ICCA Support Council to the global system including the ICCA Consortium and UNEP’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) (see Figure).

Another positive step forward is the cooperation of relevant government organizations such as the DOE and FRWO, as members of the ‘National Steering Committee’ of UNDP/GEF/SGP that have lent their support and approval to relevant GEF-SGP projects focusing and emphasizing on ICCAs under the GEF’s current fifth four-year cycle. This programme intends to devote a significant portion of its resources to projects that strengthen and develop a better understanding of nomadic ICCAs. In support of these projects there is a high level of collaboration amongst IPs/LCs and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs).

Some recent SGP-funded projects towards ICCA support and recognition include:

Restoration and management of ICCAs through conservation of biodiversity in the territory of Taklé tribe, Shahsevan confederacy;

Restoration and management of ICCAs through conservation of biodiversity in the territory of Taklé tribe, Shahsevan confederacy;

Planning and implementing Community-Based Ecotourism by focusing on territorial integrity of Heybatlu sub-tribe, Shish Bayli tribe, Qashqai tribal confederacy;

ICCA and Rangeland restoration to achieve sustainable livelihoods through traditional management of water resources and alternative forage production in the customary territory of Qurt sub-tribe, Qashqai tribal confederacy;

Reviving ICCAs in Customary Territories of Abolhassani Mobile Pastoralists— Coping with the Effects of Climate Change and Drought through Local Initiatives and Ecological Management;

Reviving ICCAs and Customary Management

of Natural Resources in Inverted Tulips Plain– Summering Grounds of the Bakhtiary tribal confederacy.

Despite recent advances, in Iran, governance and management rules for natural resources need a significant reform to achieve full recognition and support to ICCAs. There is also a need for other forms of recognition and support including documentation and research, technical, financial, developmental, advocacy, and networking support and social and administrative recognition (such as awards, or a place in governmental planning processes). Regarding legal and policy recognition, there is a need for adequate mechanisms to respect indigenous peoples and local communities (especially with regard to territorial, collective, and tenurial rights), as many of the existing policies may actually be against their interests. So it should be kept in mind that despite the very visible progress in recognizing and supporting ICCAs in Iran, there still are huge weaknesses and gaps, varying from a complete lack of legal and policy recognition to inappropriate or inadequate recognition.

The vision for ICCAs in Iran is that they will be fully recognised as entities self-governed through their revived customary institutions and laws by their own long-time associated IPs and LCs and their re-empowered federations. Their role would be recognized for both preservation and restoration of biodiversity and natural resources, as well as for sustainable livelihoods and local and national economy. Linkages between local and national organisations governing ICCAs would be as vibrant as those between international organisations and national entities.